100 Movies Every Catholic Should See #110: High and Low (1963)

Directed by Akira Kurosawa. Starring Toshirō Mifune.

As post war tastes shifted to society's seedier elements, pulpy detective novels produced en masse provided easy entertainment for a weary world. For Kurosawa, an artist of refined literary sensibilities, this ostensibly populist fare would become a surprising source of inspiration for his bracing procedural thriller, High and Low. The title itself establishes a spectrum of oppositions: beginning with the simplistic inspiration behind it, from which Kurosawa unfurls a sophisticated ethical study with the highest level of artistry. Through alterations to the source material, Kurosawa’s adaption presents a fascinating social commentary of modern Japan through the lens of natural-law morality. High and Low’s clear ethical framework draws a clean line between good and evil, even as personal convictions are tested within the film’s thrilling narrative structure. As Japanese‑cinema scholar Donald Richie observes, “morally, [High and Low] would seem to be the most black and white of all of Kurosawa's films”.1 The original Japanese title, Tengoku to Jigoku—Heaven and Hell—further alludes to this stark demarcation between the realms of good and evil, both in their moral landscape and physical setting, which unfolds in an almost Dante-esque fashion as the film progresses.

As noted above, High and Low is a study in opposites, within the structural design and the dramatic content. The first half unfolds within the glass‑walled high rise of the wealthy executive Kingo Gondo, overlooking Yokohama - the “high” in “High and Low”. A sense of order pervades amidst the modern luxuries where Gondo’s stable nuclear family suggests a social and moral equilibrium. Midway, the film plunges the viewer into the “low”: the squalor of the slums beneath the high rise, where wild lawlessness and disorder pervade, a realm of drugs, prostitutes and murder. Richie likens this contrast to the moral structure of The Divine Comedy: “In his depiction of contrasts Kurosawa follows Dante. Heaven is a measured place of muffled crisis where things as they are are insisted upon; hell is a chaos, wildly exciting, quite dangerous.”2 The main drama is catalyzed as these two realms of order and chaos collide, challenging Gondo’s moral system, and by extension, the societal structure of the entire city.

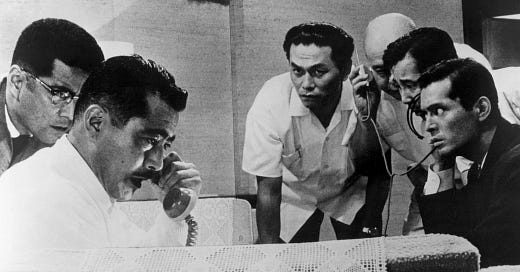

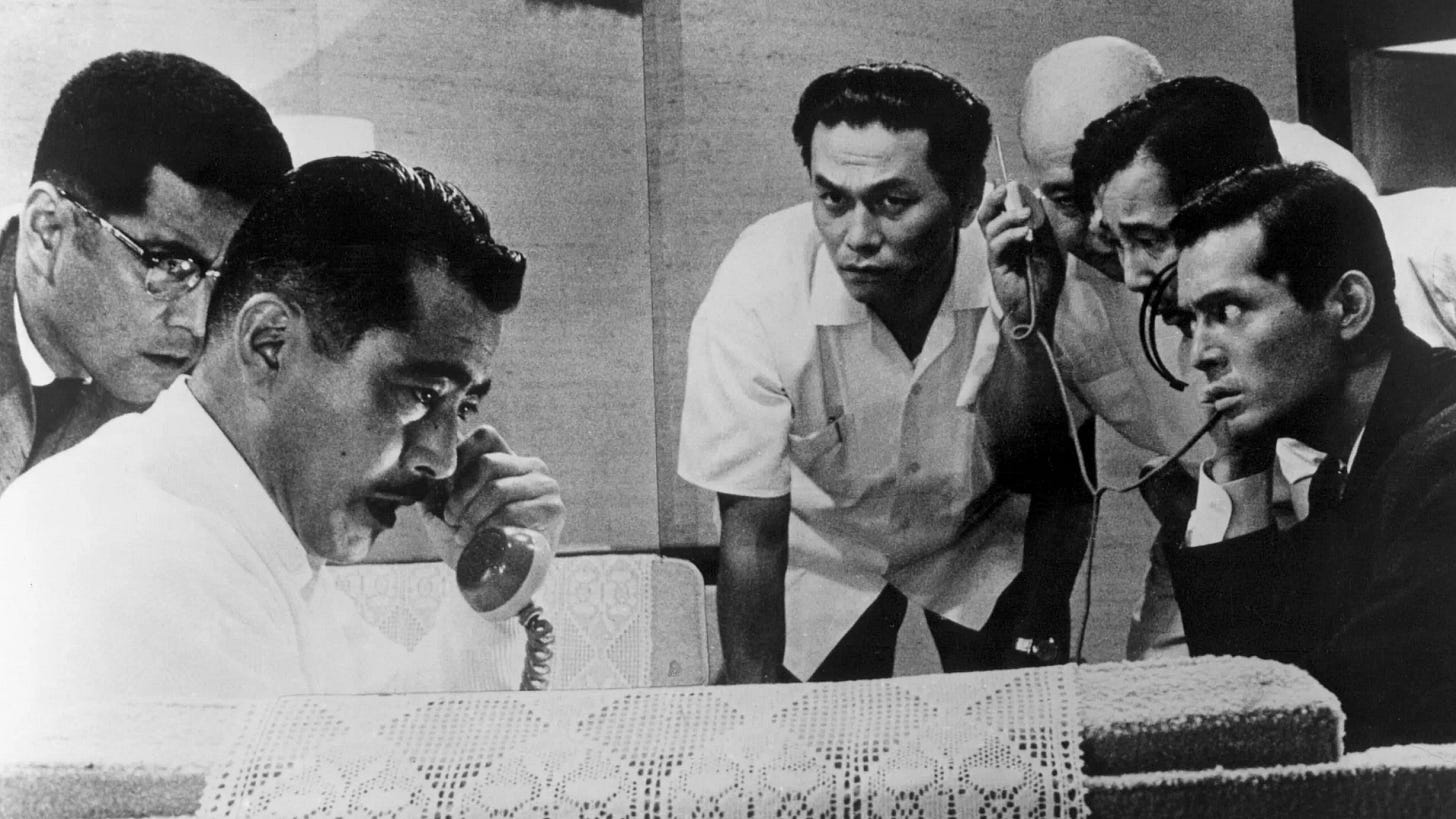

Gondo first appears as a man battling to maintain the quality of his company’s product against the desires of his peers to maximize profit through lower quality. Determined at all costs to wrest control, he executes a clandestine buy‑out of his company, National Shoes, mortgaging all his property in the process. As the plan comes to fruition and the champagne is popped, the telephone rings with the news that his son has been kidnapped. A ransom is demanded that would render the buyout untenable and that would cost Gondo all of his property. At first, Gondo immediately agrees to pay, only to learn that there was a mistake as his own son appears in the living room safe. The son of Gondo’s chauffeur was kidnapped instead of his own son. Gondo’s dilemma grows infinitely thornier.

This development represents the crux of the film’s moral question - will Gondo sacrifice everything he has been working his whole life to build and put his family’s entire livelihood in jeopardy to save a servant’s child? The tension is palpable, as Kurosawa’s claustrophobic framing follows Gonda pacing back and forth, drenched in sweat, and agonizing over a decision that will change the course of his life forever.

To fully appreciate the moral and societal dynamics at play, it is essential to consider the character in the kidnapper in relation to Gondo. He is driven by a sense of resentment for what he perceives as an unfair inequality, later confessing “I do know my room was so cold in winter and so hot in summer I couldn't sleep. Your house looked like heaven, high up there. That's how I began to hate you.” His spite is impersonal: Gondo has done nothing to him; but rather merely presented a palpable symbol of privilege. Kurosawa paints the kidnapper in a suitably unflattering light. Modern interpretations often lean towards a shallow reading of the film as an indictment of capitalism. But, the nature of the kidnapper’s character complicates, if not outright refutes, such arguments. As Richie notes, “In this film there is not the slightest sympathy for the villain nor for the world that is his…the villain is truly black.”3 There is no misunderstood working class victim here. Rather, at the conclusion, Kurosawa shows that his envy not only has the eventual effect of putting more money into the pockets of Gondo’s greedy peers, but also unravels the societal order by dismantling Gondo’s lifetime of hard work. Richie surmises that “by the end the bad man has become thoroughly subject to those very actions through which he sought to free himself.”4 The forces of Kurosawa’s “hell”, personified by the envy of the kidnapper, are destructive and chaotic. The morals are clear.

Returning to Gondo, he is forced to weigh the worth of a human life against the fortune he spent a lifetime building. Something Kurosawa does so well in his films involves forcing his seemingly unassailable protagonists to descend from a position of security and strength to risk losing everything in defense of the helpless and innocent. This element can also be observed in his preceding 1961 film, Yojimbo, where the nameless ronin puts himself in grave danger to protect an innocent family as they escape a bloodthirsty band of outlaws. Gondo, guilty only of class position, makes the difficult decision to forfeit his livelihood to save the life of another man’s son. While the sacrificial nature of Gondo’s ultimate choice easily jumps out to Christian audiences, Kurosawa’s likely intent was to portray the Zen‑Buddhist ideal of gaman: enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity. Richie further notes that Gondo’s admirable quality “is mainly that of his being able to tolerate the idea of beginning again, of his being willing to accept a meaningless disaster for which he could in no way be considered responsible, of his finding the strength to continue, his ability to believe in himself.”5 Whatever interpretive moral lens one takes, one point is clear - Kurosawa stands on a firm ethical foundation: virtue and vice are oppositional, and right and wrong are not negotiable.

High and Low’s suggestion, then, is that right and wrong are not inherently tied to the class identity, revealed through the moral choices each man makes when confronted with adverse circumstances. The kidnapper is not in the wrong because of his humble class, but because he chooses to embrace hatred and envy as his modus operandi, defining himself by resentment and claiming victimhood as justification for evil. In contrast, Gondo embraces a costly but virtuous path, putting a human life above his wealth, accepting the burden to endure the resulting hardships and begin again, even at the cost of his status. Contemporary films, Parasite in particular, which drew inspiration from High and Low’s exploration of class disparity, often adopt a framework of sticking it to the rich, excusing the immorality of the oppressed lower classes as an understandable, if not a desirable response to being impoverished. While High and Low seeks to starkly illustrate the opposing experiences of rich and poor, ultimately, it resists such frameworks. The film insists that moral character is not determined by social standing but by how each man acts: their free choices define whether they embrace Tengoku or Jigoku - Heaven or Hell.

For Catholic viewers, High and Low presents a compelling exploration of a clearly defined moral order, grounded in natural law. Kurosawa’s profound understanding of human nature, along with Western sensibilities, particularly his affinity for Dante makes this film highly accessible, even more so than some of his Samurai films due to the contemporary setting. This lesser known venture, made at the height of Kurosawa’s creative powers, serves as an ideal entry point into his renowned filmography. Right and wrong do not change with circumstance, they remain constant no matter the time, place, or class.

Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa, 3rd ed., expanded and updated (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 166.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., 167.

Ibid., 166.

I had struggled with Kurosawa and what I had interpreted as a campiness in the past, the introductory essay to this series convinced me to give High and Low a chance and I was blown away. What a powerful, fascinatingly constructed film. I am proof that it is indeed a great introduction to Kurosawa and am very glad you wound down the series with some great thoughts on this one!

This was a splendid essay to read. I have seen several Kurosawa films, but I have neglected High and Low. Now I am strongly motivated to see it, especially considering that Spike Lee has just made a new movie based on it, Highest 2 Lowest.