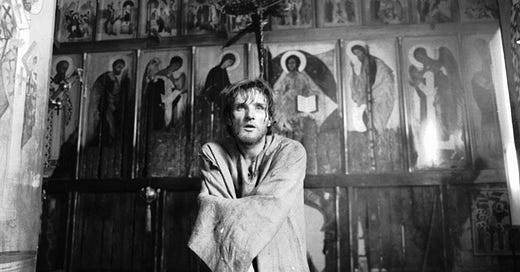

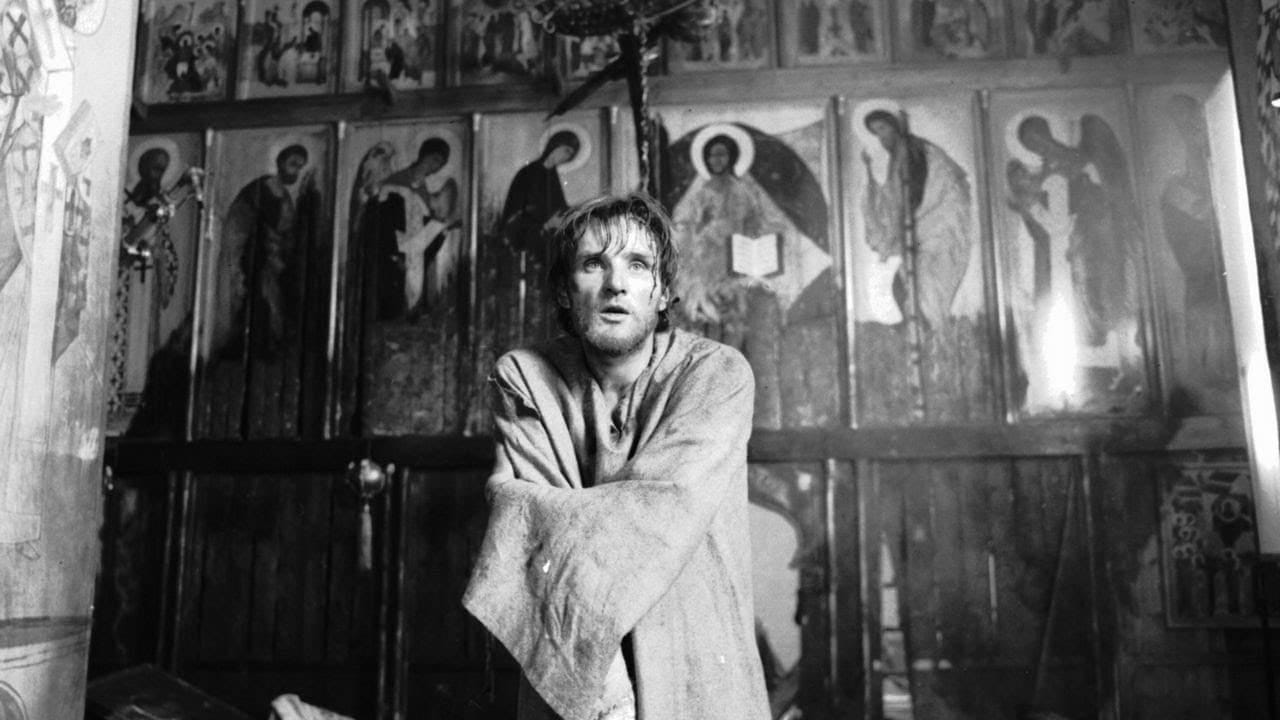

100 Movies Every Catholic Should See #47: Andrei Rublev (1966)

Directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. Starring Anatoly Solonitsyn.

Writing on Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1966 epic, Andrei Rublev is truly a daunting task given the grandeur of its scale and the profundity of themes it explores. Lauded by secular and Christian film critics alike, Andrei Rublev stands as one of the great achievements of the cinematic artform over the past century. BFI’s Sight and Sound Greatest Films of All Time, a preeminent and universally respected list, asserts that Andrei Rublev “may be the most wrenching depiction of belief, creativity and the search for meaning ever filmed”.1

A quick look at Andrei Tarkovsky and his philosophy will be helpful in unpacking everything this film has to offer. Tarkovsky emerges from behind the relative secrecy of the Iron Curtain as an enigmatic figure, shrouded in a sense of spirituality and a deep intellectual sensitivity. He viewed the art of filmmaking as on par with the classical fine arts of music, painting, and sculpture, with the power to move man’s spirit beyond the realm of the merely physical. “The primary function of cinema is to reveal the invisible, hidden layers of reality”2 he asserts in his foundational artistic credo, Sculpting in Time. As the title suggests, Tarkovsky viewed the essence of the director’s work as that of a sculptor, except in this case, the block of marble has been replaced with the linear existence of time from which he brings forth an experienced reality of its own. Tarkovsky’s work is imbued with a sense of the spiritual. Though certainly not without his flaws, Tarkovsky’s Christian orthodox faith has permeated throughout his filmography, offering the thoughtful viewer a meditative and prayerful experience. Utilizing long immersive shots, often of natural textures and long periods of silence, his films invite one to slow down and become aware of greater spiritual realities. For the Catholic viewer, a Tarkovsky film presents a unique and cherished opportunity to examine the interplay of the nuances of their faith with the most prevalent art form of this age.

Within its three hour runtime, Andrei Rublev manages to encapsulate much of the human experience, from love, jealousy, guilt, war, atonement and faith. As with all great works of art that have stood the test of time, the film speaks to the universal human condition with a message that will resonate with viewers from this generation and those hundreds of years to come. How Andrei Rublev came to be and the details of its difficult release offer further nuance in the appreciation of its brilliance.

The historical figure of Andrei Rublev whom the film is based on occupies a preeminent position in Russia’s national identity and the history of art as a whole. With a life spanning the 14th and 15th centuries, Andrei Rublev is widely considered one of the greatest painters of Orthodox Christian icons. His style has been emulated to this day, and chances are that any icons hanging in the homes of those reading this article take inspiration from his work. Tarkovsky’s inspiration for his film was not simply biographical, he wanted to explore the relationship of the artistic journey through the lens of the time he lived, and through it, offer a meditation on the nature of faith’s relationship with art. In the Soviet Union, artists faced heavy censorship and often a dangerous and arduous process in bringing their creative works to fruition. Films in the West often met challenges in securing studio funding and approval, but in the East, Tarkovsky had to contend with an oppressive state apparatus and multiple rounds of censor reviews for his work to see the light of day. Due to the film’s themes of faith, artistic freedom and obscurantism, the state authorities immediately censored it upon its 1966 release, with a recut version finally making its way to the wider world in 1971. Through the dedicated work of film preservationists, most notably Martin Scorsese, who traveled to Russia years later and purchased the film reels of the original cut, audiences today can enjoy the film as Tarkovsky originally intended.

Diving into the film itself, one of the themes that immediately becomes apparent is the relationship between faith and art. In many ways, much of the film can be interpreted autobiographically, or at least as a working out of some of Tarkovsky’s own inner thoughts. Little is known about Andrei Rublev’s life, leaving many elements of the narrative open for Tarkovsky’s interpretation. That is not to say that the film is historically inaccurate, as Tarkovsky and his crew spent years studying medieval manuscripts and medieval art in preparation for production. What Tarkovsky seemed most interested in portraying was the spirit of the age, and the relationship of the artist to his time and to the events surrounding him, from major political shifts to the nuances of Orthodox spirituality found in the Andronikov Monastery where Andrei lived as a monk. Against this epic canvas, Tarkovsky is able to draw out Rublev’s struggle against doubt, guilt, and lack of faith in accepting his God-given artistic talent.

In simple terms, one can look at this film as a purgative journey which Andrei must undergo in order to accept and embrace his vocation to create beautiful and truthful art. Art and suffering are interrelated. This is something Tarkovsky himself knew all too well, yet he viewed the suffering as redemptive, and ultimately eschatological, stating that “the aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.”3 At the beginning of the film, Andrei’s brother monk Kiril points to the fact that though Andrei’s art is renowned, it lacks the vital ingredient of faith.

They praise him, that's right. He puts the paint in a thin layer, very delicately, very skillfully. But something is missing...Fear is missing, and faith! The faith that comes from the bottom of one's heart.

Over the subsequent events of the film, Andrei wrestles with temptation, faces betrayal and ultimately struggles with guilt and the sense of his own worthiness in the eyes of God. He receives a prestigious commission to decorate the walls of the Cathedral of the Annunciation in Moscow and Kiril, his faithful companion, rejects him in a fit of jealousy. On his way to Moscow, Andrei finds himself amidst a pagan ritual in which he is beset on all sides by temptations of the flesh. The scene is visceral and hellish, a bachchan cacophony from which Andrei struggles to tear himself away from. In the end, he lets his curiosity get the better of him and lingers. A weight of guilt seems to descend upon him as he continues on to Moscow. Rublev finds himself unable to start his new commission, confiding to one of his companions that he has lost the peace of mind necessary for an artist to paint. Matters only worsen later on, when the Tartars raid the city and Andrei kills a man defending an innocent life. Andrei is further wracked with guilt. And here is the crux of the matter, for Andrei knows intellectually that God will have mercy on him, yet he lacks the faith to believe it in his heart. A mentor offers him sage advice, telling him that “God will forgive you, but you must not forgive yourself. And go on living between His forgiveness and your own torment.” Andrei chooses to embrace a vow of silence instead, believing he has nothing left to offer the world and that this will be the only thing he can do before God to atone for his sins. “I'll never paint again..nobody needs it.” he laments.

Herein lies the great lesson of this film. Christ teaches in the Parable of the Talents and again in the discourse on the lamp under the bushel basket that one’s God-given gifts are not to be squandered and hidden away. The vocation of the artist involves using their talents to reflect God’s truths in the world, so that others may be drawn closer towards a union with God. “You are the light of the world…your light must shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your heavenly Father.” (Matt 5:16). Had Andrei’s decision remained, the world would have been deprived of the great truths which his paintings convey. Rublev’s renowned icon Trinity remains one of the most profound portrayals of the great trinitarian mystery ever brought forth in an artistic medium.

Fortunately, in a magnificent final sequence involving the casting of a great bell, Andrei finds his faith, moved as he watches a young boy lead a team of craftsmen in a grueling process to pour molten metal into a cast in the ground to bring forth the bell. It is a great act of faith, as none of them are assured that the bell will sound following their arduous, days-long process. The symbolism of bells in the Russian Orthodox tradition cannot be understated. To Orthodox Christians, bells are seen as “singing icons”, the aural compliments to iconography in portraying the truths of gospel. The bell in this sequence points to the internal resurrection of Andrei Rublev, the completion of his purgative journey and his awakening anew with the eyes of faith. Entire books could be written on this sequence alone, as it represents some of the finest depictions of the Christian faith ever put to cinema. As the boy who led the casting of the bell sinks to the ground in utter exhaustion, Andrei, moved to tears reaches out a comforting hand, imparting these hopeful words:

We'll go together now. You'll be casting bells, and I'll be painting icons. We'll go to the Trinity, you and me. You've created such a feast, such a joy for people.

Andrei has found his faith, and through it, the spark of his artistic inspiration. It is fitting that in an earlier version of the film, Tarkovsky had chosen the title The Passion according to Andrei. It is through redemptive suffering and learning to have faith in God’s forgiveness and love that Andrei is finally able to fully embrace the talent’s that God gave him and be a light to the world.

Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev represents an essential viewing for any Catholic interested in film. Casual viewers should not be dissuaded by its 3 hour runtime and Russian language, it is well worth the effort. One should not feel discouraged if they do not understand everything on a first viewing. One of the joys of great cinema involves being presented with many ideas that may not seem apparent at first, but spark further meditation and conversation afterwards. The writer of this article spent several weeks pondering and discussing this great film prior to putting thought to paper. This Lenten season presents a perfect opportunity to deepen one’s faith. Film has the potential to elevate one’s mind and soul to God just as all art that is true, good and beautiful. The world has been truly blessed by artists like Andrei Rublev and Andrei Tarkovsky who have embraced their vocations and let their lights shine for the benefit of all humanity.

https://www.bfi.org.uk/film/f76e5f6e-6cdc-5a9e-afd9-34aa854e59a6/andrei-rublev

Andrei Tarkovsky. 1987. Sculpting in Time : Reflections on the Cinema. Austin, Tx: University Of Texas Press, 21.

Ibid., 43.

I've never heard of this film before! Where can I stream/watch it?