100 Movies Every Catholic Should See #20: The Reluctant Saint (1962)

Directed by Edward Dmytryk. Starring Maximilian Schell.

“Joy is the noblest human act” - St. Thomas Aquinas

When I was a student in Rome my junior year of college we went as a class to both Siena and Assisi for a week-long pilgrimage. On the close to two hour bus ride between cities the staff put on Michael Curtiz’s 1961 film St. Francis of Assisi to better get us in the right mood for our arrival at the saint’s old home.

I’m not sure we ended up finishing it, but it didn’t really matter because I don’t think a single person on the bus was engaged with the film: suffice to say it was very boring (apologies to anyone who may have nostalgia for this film). It was extremely self-serious and static, very atypical of the kinds of epic Biblical fare that had dominated the box office in the decade before it was released but was quickly becoming trite and cliched.

Interestingly enough, a year later director Edward Dymytryk independently financed a film based on the life of St. Joseph of Cupertino well outside the domain of the studio system. Having worked on B-movies throughout the 1940s, here was a director who was good with money and was not going to produce something extremely lavish like a Cecil B. DeMille. That’s not to say that there was anything wrong with the extravagance of those kinds of films, but they often focused more on spectacle than any sort of spiritual nuance.

The Reluctant Saint for all intents and purposes is a film that is as humble and unassuming as its protagonist, while also maintaining the unique joy and mirth that is often excluded from the typically austere depictions of saints both in writing and in cinema. Towards the beginning of his biography of St. Francis, G.K. Chesterton writes on all the different ways one can approach writing on the life of a saint, and concludes that “the reader cannot even begin to see the sense of a story that may well seem to him a very wild one, until he understands that to [St. Francis] his religion was not a thing like a theory but a thing like a love-affair”. To focus only on historical accuracy or the most austere qualities of a saint would fail to fully convey the simple happiness these holy men and women radiated in even their smallest of deeds.

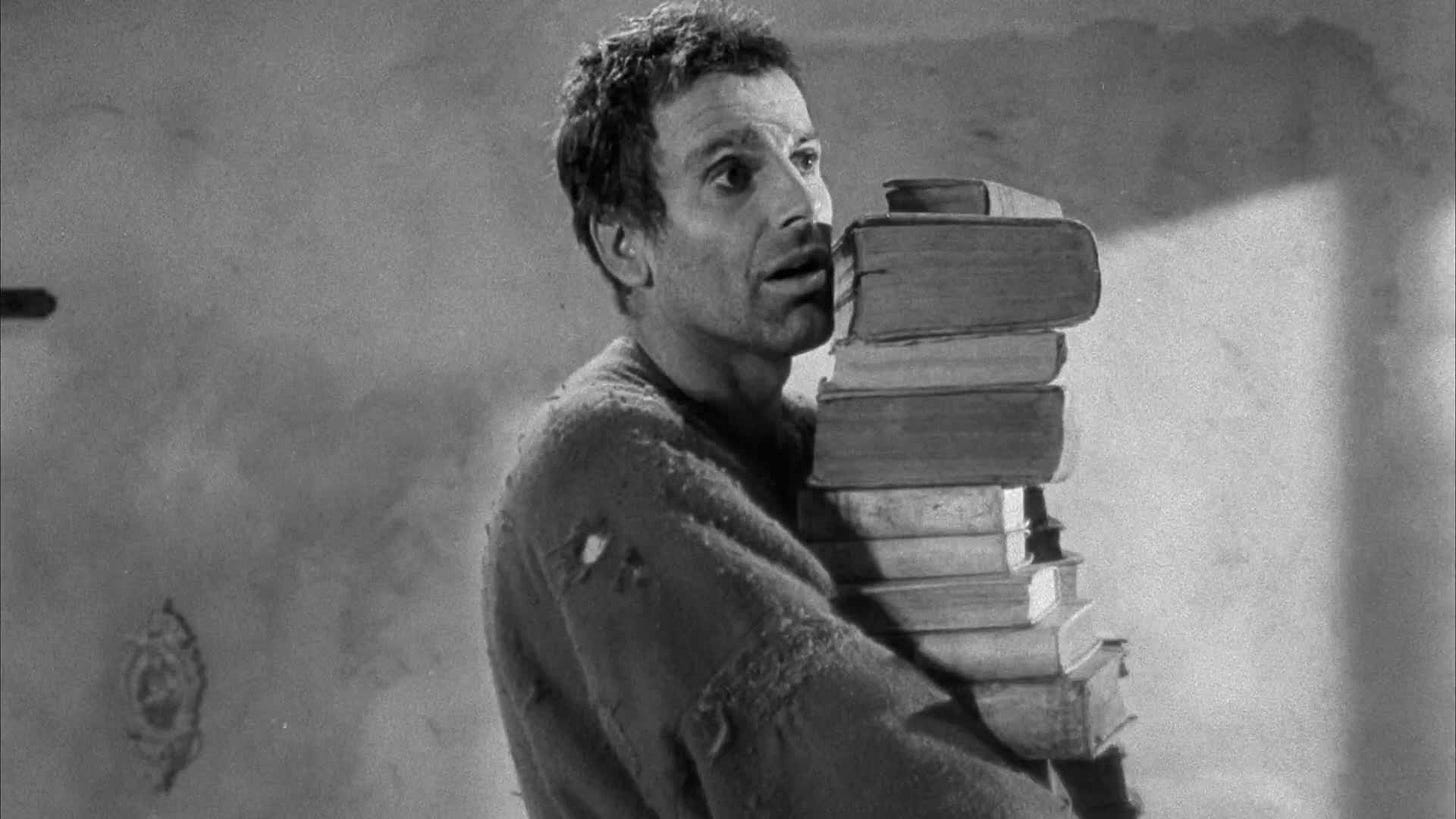

This simplicity is conveyed perfectly in St. Joseph- referred to as “Giuseppe” by everyone in the film- by Maximilian Schell, who had just come off an Oscar win for Best Actor the previous year for a far more serious role in Judgment at Nuremberg. The portrayal of Giuseppe is very much a comedic one- he lives with his hot-tempered Italian mother (scene-stealer Lea Padovani) and is seen by most to be a clumsy, bumbling oaf who will never amount to anything. And yet it never veers into parody; amidst his struggles with school and his child-like simplicity, what is really striking about Giuseppe is his joy and sincerity, especially after joining the Franciscans (at the insistence of his mother).

After accidentally destroying a centuries-old statue of the Virgin Mary in the courtyard and being temporarily dismissed from the order, Giuseppe is taken back in- only after a hilarious scene in which his mother chews out his uncle, the abbot (Harold Goldblatt) in front of the whole order. He is therefore given the lowest of tasks, living and working in the stable, where his clumsiness will not create such a hazard. The reaction from Giuseppe however is unexpected: he is thrilled. Not only does he get to work with his beloved animals, but he is also free to work completely on his own without any scrutiny from overbearing mothers or the brothers who question his being admitted into the order. He saves the remaining head from the broken Mary statue and places it by the sole window high above his bed and kneels deep in prayer every night. The joy and diligence he exemplifies in the most thankless and exhausting of jobs is inspiring, and others slowly begin to take notice.

The monastery is visited by Bishop Durso (Akim Tamiroff), and from his introduction he has clearly become a little jaded in his role amidst the bureaucracy and fine living that accompanies his role. While the abbot and Fr. Raspi (notable Catholic actor Ricardo Montalban of Star Trek fame) attempt to divert the bishop from the stables on their tour for fear of Giuseppe causing another scene, they eventually fail to sway him and show up at the stables to find our protagonist fast asleep in the hay. Furious, his uncle wakes him up and demands an explanation, but to the bishop’s delight all is explained when the soft cry of a baby lamb is heard: Giuseppe stayed up all night with the mother lamb while she gave birth. Admiringly, the bishop picks up one of the lambs, and gazing off into the distance recites Luke 15:4: “What man among you having a hundred sheep and losing one of them would not leave the ninety-nine in the desert and go after the lost one until he finds it?” The quote stays with Giuseppe, and, humorously, in his later studies for the priesthood (as mandated by his new friend the bishop) it’s the only quote from the Bible he can remember.

The entire movie is filled with humorous yet poignant scenes like these, and the fantastic ensemble does a great job moving between pathos and comedy. Laced throughout is a beautiful and memorable score by the legendary Italian film composer Nino Rota (The Godfather) which fits perfectly with the authentic locations throughout the Lazio region of Italy where Dmytryk chose to film, not far from the real Cupertino. Any sort of cinematic extravagance is eschewed in favor of character moments that make these centuries-old figures feel wholly real and relatable. Schell’s St. Joseph of Cupertino serves as a model for us for how to live our lives with joy even in the toughest of circumstances, because we can always rejoice in the overabundant love our Lord wishes to share with us in every moment of our lives.

St. Joseph of Cupertino, pray for us!

“For even though the fig tree does not blossom, nor fruit grow on our vines, even though flocks vanish from the folds and stalls stand empty of cattle, yet I will rejoice in the Lord and exult in God my savior” (Canticle of Habakkuk 3:17-18)

"Any sort of cinematic extravagance is eschewed in favor of character moments that make these centuries-old figures feel wholly real and relatable." Perfectly sums up the film.

I loved that Ricardo Montalban was in this film. It helped me identify with the seriousness of the monks versus the childlike playfulness of Guiseppe.