100 Movies Every Catholic Should See #104: The Searchers (1956)

Directed by John Ford. Starring John Wayne and Jeffrey Hunter.

As a director, John Ford was notable for delivering quality in bulk. The great critic Andrew Sarris identified at least thirty Ford films that he believed to be of “special interest” in his book The American Cinema. Even his choices omit well-regarded works like The Iron Horse, 3 Godfathers, and Drums Along the Mohawk.

But ask a critic today to name a favorite John Ford film, and the odds are he will select The Searchers from the dozens of possibilities. That would have come as a surprise in 1956, the year the film was released. As Joseph McBride documents in his excellent biography of Ford, The Searchers was a commercial hit, but a critical flop.1 It was completely ignored by the Academy, receiving zero Oscar nominations. (Around The World In 80 Days, regarded today as among the flimsiest Best Picture winners, took home the hardware that year.) Beginning in the 1960s, critics like Sarris and Peter Bogdanovich elevated the artistic reputation of Ford generally, and The Searchers specifically. The film became a touchstone for great directors who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s, like Steven Spielberg (who imitated The Searchers when making films in his friend’s backyard as a seventh grader) and Martin Scorsese (who claimed that he watched the movie “once or twice a year”). In 1972, The Searchers cracked the top twenty in British Film Institute’s decennial critics’ poll of the greatest films ever made.2 It has been on the list ever since, and ranks fifteenth in the current version of the poll, conducted in 2022.

What explains the movie’s durable appeal? For one thing, The Searchers has a gravity and seriousness that isn’t necessarily present in all of Ford’s movies. Ford primarily viewed himself as a popular storyteller and entertainer, not an auteur. To be sure, he didn’t shy away from dark material in his career, whether early (The Informer), middle (They Were Expendable) or late (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance). But The Searchers stands apart for both the gravity of the material and the presence of a swaggering anti-hero as its key protagonist. The Searchers tells the story of Ethan Edwards, played by Ford’s favorite star, John Wayne. He arrives on the Texas frontier at his brother’s house, unannounced, three years after the end of the Civil War. Ethan is bitter about the war’s outcome and living on the fringes of society. Ford’s prowess at delivering emotional and narrative context in a nimble, efficient way is on full display in these opening scenes that introduce Ethan, perhaps the finest in Ford’s entire canon. In his essay on Ford in The American Cinema, Sarris in particular praises a short, three-shot sequence which suggests that Ethan and his brother’s wife, Martha (Dorothy Jordan), have a more complicated relationship than anyone is willing to acknowledge on the surface.3

Shortly after his arrival, Ethan is conscripted into the Texas Rangers by the Rev. Captain Clayton (Ward Bond) to pursue a neighbor’s stolen cattle. The heist proves to be little more than a ruse for a “death raid” by a band of Comanche Indians led by their fearsome war chief, Scar (Henry Brandon). The Comanche murder Ethan’s family except for Debbie, his niece (played as a young adult by Natalie Wood), who the Comanche abduct. Ethan, consumed with racial hatred for the Comanche even before the attack, vows revenge and begins a years-long search for Scar and Debbie. Ethan is accompanied through the search by Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), an adopted member of the family of Ethan’s brother. Martin’s Indian heritage and affection for his adopted family leads him to serve as a voice of restraint the film, a voice that Ethan is, at best, reluctant to heed.

Despite the gravity of the underlying story, The Searchers retains the lightness and grandeur that is so characteristic of Ford’s films, making them a place of artistic shelter in a storm of changing aesthetics. There is Monument Valley, in this film like so many others both a setting and a character unto itself, remorseless and beautiful. There are the thunderous chase sequences, so reminiscent of those in movies like Stagecoach and the “US Calvary Trilogy” (Fort Apache, Rio Grande, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon), yet never losing their capacity to thrill. There is Ford’s “stock company,” quietly delivering wonderful performances up and down the cast. The best lines in The Searchers come not from one of the stars, but from Olive Carey, the mother of Ford regular Harry Carey Jr.; she plays the mother of Martin’s paramour, Laurie Jorgenson (Vera Miles).

Then there is the constant juxtaposition of conflicting aspects of human nature in which Ford’s films delight. In particular, for a movie about the hunt for mass murderers, The Searchers is surprisingly deft in its use of humor. Ford was underrated as a director of all kinds of comedy, both verbal and grasped, and he grasped the importance of levity even in the midst of a serious dramatic work. The profane and the sacred are never far apart in this film. Ethan walks out early on a funeral to start hunting down Comanches; a wedding is preempted by a knock-down, drag-out brawl; the Texas Rangers praise the Lord while shooting their pursuers. Ward Bond, whose character is both a preacher and a captain of the Texas Rangers, is the walking embodiment of this ideal in Ford’s films. Everyone should love something in life as much as Bond enjoys watching two young men come to blows over a romantic rivalry.

But ultimately, the enduring fascination with The Searchers, and the reason it stands apart from Ford’s other films, is Ethan, a John Wayne hero (or anti-hero?) like no other. Ethan drives the search for Debbie; the older settlers have no time to continue the search, and the younger ones are too impulsive and inexperienced, at least at first. But the vengeance that drives Ethan—a vengeance so strong that he is willing to kill a member of his family to attain it—cannot be countenanced by his more respectable companions. And as Joseph McBride observes, the sweat of Ethan’s brow is not enough to overcome Scar; Martin must play a decisive role in the final raid in order to save Ethan from indulging his worst impulses, and prevent further tragedy to his family and his community.

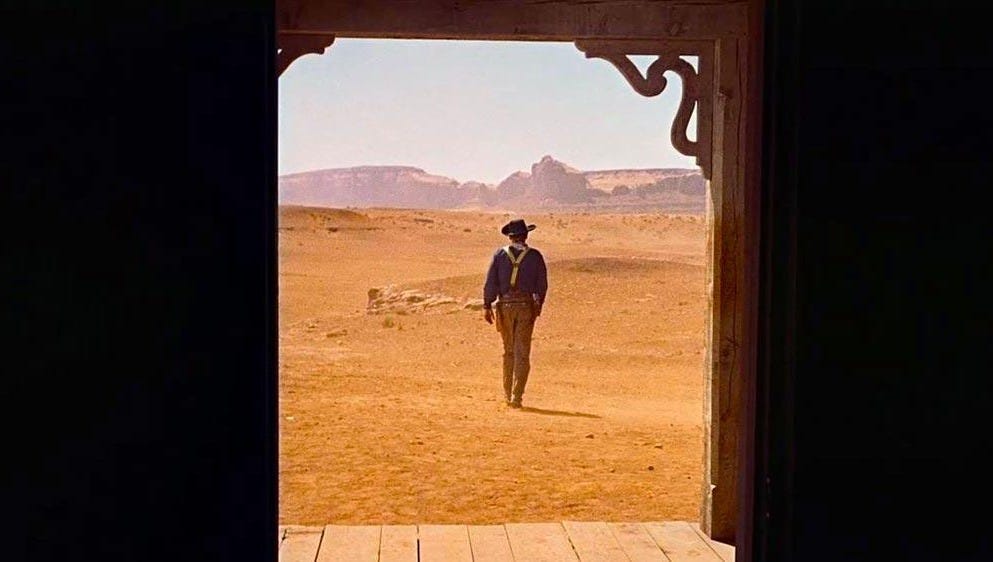

Much of The Searchers’ comic relief is provided by Mose (Hank Worden), a kindly but senile farmhand. The choice of that name is unlikely to have been accidental; Ford was a lifelong (but not particularly devout) Catholic. Ethan wanders the desert for years searching to satisfy his twisted heart. He ends the movie at the threshold of a new era of peace, but like Moses, he is not meant to enter that new era; the movie’s final shot shows him at the threshold, moving no further. Rather, it is Martin and Laurie who appear set to enjoy the fruits of a more peaceful future. “Some day this country's gonna be a fine, good place to be,” Mrs. Jorgenson says, ruing her son’s death at the hands of the Comanches. “Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.” The paradox of the anti-hero sacrificed so civilization can move ahead was a perennial fascination for Ford, and one that continues to draw us to The Searchers some seventy years later.

Joseph McBride, Searching for John Ford (St. Martin’s Griffin 2003)

British Film Institute, Sight and Sound Magazine, “Critics’ Poll: The Searchers” (Accessed April 6, 2025)

Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema (Dutton 1968)

This moving is an absolute must see. It's great.

One of my favorite movies. We watch it any time it's on. A must see.