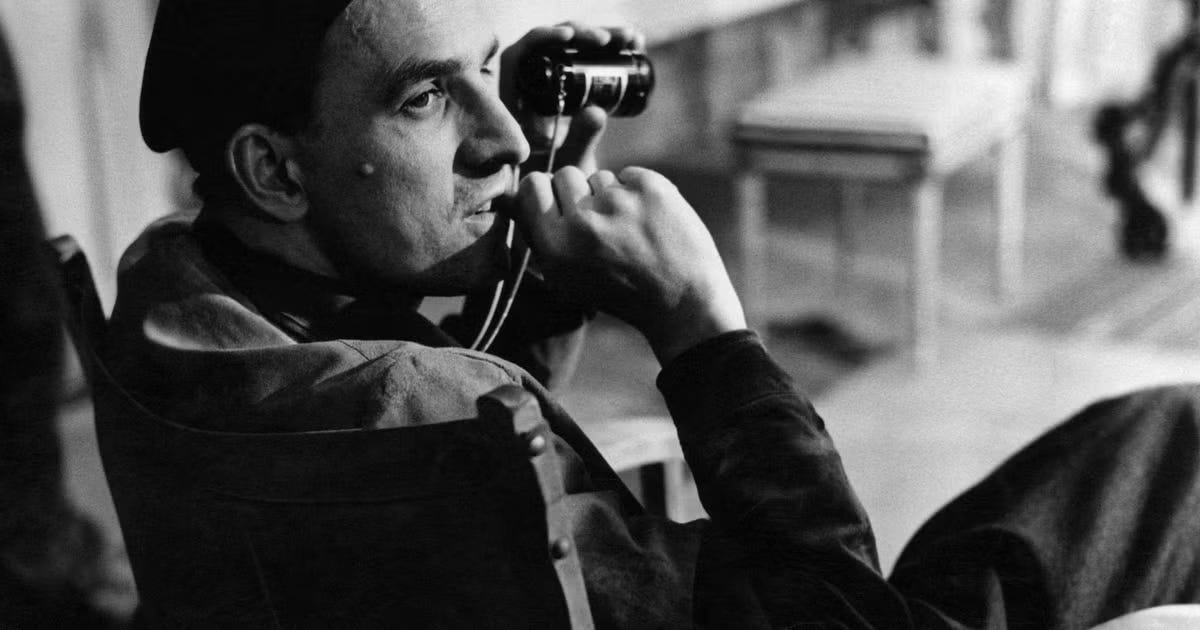

Introducing '100 More Movies' Series #3: The Films of Ingmar Bergman

A journey through the work of the renowned Scandinavian auteur

God writes straight with crooked lines

Following our journey through the epic and grandiose storytelling of Kurosawa, we now travel to Sweden to discuss another master of his craft: Ingmar Bergman. Bergman’s name is synonymous with dense and artistic storytelling. His work is more difficult to approach than most filmmakers and is better known in smaller international film circles. While not all of his vast body of work is perfect, he has a body of work that stands head and shoulders above almost all other filmmakers, and more than deserves a place on the Mount Rushmore of international auters.

Oddly enough, it seems that despite being an imperfect messenger, Ingmar Bergman has a message worth experiencing. Bergman’s work is some of the most challenging yet rewarding cinematic works ever put to film. To not recommend him to anyone interested in film would be a criminal disservice to them and deprive them of one of cinema’s greatest innovators. The performances and images he was able to consistently produce over the course of 60 years are nothing short of awe-inspiring, and serve as a masterclass of the sheer power that film can have.

Bergman’s early work in the 1940s would thematically and stylistically lay the groundwork for the rest of his career. In films such as Summer Interlude or A Ship to India (his only noir), he would focus more intently on relationships and small casts. His 1940s work is difficult to find, but shows his young prowess as an impactful storyteller being honed.

The bulk of Bergman’s well-known work begins in the 1950s. Beginning with Summer with Monika, Bergman would establish himself as a challenging and sometimes provocative filmmaker. Despite its topic being about a summer fling with an excessively affectionate Monika, the film serves as a condemnation of the “fast and loose” lifestyle that seems quite popular in our current era. This would also begin a trend within Bergman films where the themes do not seem to necessarily match with his own personal lifestyle or beliefs. Despite his bitter relationship with his Lutheran father (who frequently was quite cruel to him) most of Bergman’s religiously rich cinema comes from his 1957-1963 era. His obsession with the macabre, faith, and relationships was perfectly blended in stunning yet frequently devastating films such as Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal (both came out the same year), Through a Glass Darkly, The Virgin Spring, and Winter Light. All of these films remain under 100 minutes apiece with very small casts and even tighter scripts, but what they lack in length, they more than make up for in power. One of Bergman’s most endearing traits as an artist is how much he is able to do with so little. Ingmar himself described that he wants audiences to “feel his films, rather than totally understand them”. This prioritization helps with rewatches, and allows the audience to engage with his art in a different way, and gives new perspectives on their messaging depending on what stage of life you are viewing them at.

The Seventh Seal was my personal entry point into his art, and I would recommend those desiring to acquaint themselves with this new filmmaker to start with either it or Wild Strawberries.

It is also worth noting that Ingmar Bergman’s real strengths as a filmmaker, above all, lie in the performances, characters, and cinematography. In the 13 Bergman films I’ve seen, I have never seen a performance that was anything less than great. Almost all his films deal with very small casts of repeat actors who were repeats for a reason. Legends such as Max Von Sydow, Bibi Andeerson, Liv Ullmann, Gunnar Bjornstrand, and Ingrid Thulin consistently are pushed to their limit in their many respective appearances throughout Bergman’s illustrious repertoire. Tying into this, every character feels so real it can be surreal at times. Every character in every film is so complex, vivid, and expertly written there never feels like there is fat to his films. Ingmar Bergman is particularly known for his female characters, who do not fall into tropes, but rather feel complex and tangible. He was particularly fond of women as his subject matter, and has multiple pieces that only feature women. Where Bergman separates himself from modern attempts at this is he is interested in femininity, as opposed to feminism. His focus and admiration for femininity is constant throughout his cinema, adding a layer and voice that should be noted by modern filmmakers. Finally, the cinematography of Ingmar Bergman’s cinema is perhaps some of the best that the art form has to offer. Over the course of his career, Bergman worked with 3 cinematographers, with the most notable being Sven Nyvisk. Together, Sven and Ingmar would revolutionize cinema, with each collaboration giving a collection of shots that would be worthy of an art gallery. In my own personal collection, the item that consistently gets people to stop in their tracks is the Bergman Criterion boxed set, which features a shot from Persona (1966) that is nothing short of mesmerizing. The same can be said for all of his films, and whether they are black and white or in color, every frame from a Bergman film truly is a painting.

Bergman would then enter his next phase as a filmmaker after Winter Light, with his most intense and provocative work. From 1963-1972, Bergman would make his most difficult and extreme works, all of which are excellent but not all for the faint of heart. The Silence would depict the direness and collapse of a family in the face of a war, and would not shy away from intense subject matters. And then, there is Persona. While it is in my personal top 10 of all time, it is quite difficult to recommend. Released in 1966, Persona is perhaps one of the most dense and challenging art films ever made. With 5 actors and 84 minutes, Ingmar Bergman redefined what cinema could be. Persona delicately, respectfully, and above all insightfully touches on topics like infidelity, abortion, the value of life, religion, guilt, career vs family, and mistaken identity to the point where, afterward, the viewer may be confused as to what they watched, which makes it a sort of cinematic Rorschach test. Again to reiterate and expand, Persona changed the game as to how faces were shot in cinema, and the effect can be seen to this day.

Bergman would follow up Persona with The Hour of the Wolf, which legitimately feels like the original A24 horror film, but done exceptionally well and with purpose. His stretch of films of Shame, The Rite, The Passion of Anne, and Cries and Whispers paint a portrait of the artist at his bleakest and darkest, with undeniable brilliance and depth present in all of them. Cries and Whispers especially is the most unusual of the bunch, where Bergman creates an image of a family so dysfunctional it would make the Roy family from Succession seem as a model family. Cries and Whispers also features Bergman’s best use of color, extreme imagery and content, and unusual collaboration, where he would collaborate with Roger Corman (king of the B horror movies) to distribute the film. Of this lot, I would say Shame is his most palpable for general audiences for sure, but if you are in love with his work there is so much quality to be seen in this era of Bergman.

In Bergman’s final phase, he would tone back his provocative nature and focus more on relationship based cinema, opening with Scenes of a Marriage. Scenes of a Marriage served as a template for later films such as Kramer v. Kramer and Marriage Story, all being based around a marriage failing in slow motion. Bergman went as far to base Scenes of a Marriage off of one of his 4 failed marriages, using the screen as a sort of confessional for his own shortcomings. This level of vulnerability is what really helps put Ingmar’s work out on its own, as almost no other filmmaker would be willing to be this open with general audiences. His last film Sarabond (2003) would bring closure to this story, but it is still a long (169 minutes for theatrical and 283 minutes for the full Tv series, the latter which is recommended) and a sad look at what happens all too often in the world. Bergman followed this up with I believe his magnum opus from this era, Autumn Sonata. Starring the Hollywood legend Ingrid Bergman (no relation to him), Autumn Sonata is a deep and vulnerable dive into the relationship of a mother and her daughters. It is nothing short of an elegant masterpiece, and is an absolute must see for anyone interested in the artform.

Ingmar would end his career technically with his epic Fanny and Alexander. This is easily the most complex to discuss on this list, and has some larger implications on his body as a whole. Throughout his long career, Bergman discusses religion and relationships consistently. He journeyed through well, giving us wonderful insights into the value of faith and the hope that is needed to survive. All of this, to crash the plane at the end. Fanny and Alexander is a monstrous 188- 312 minute epic that serves as a semi autobiographical conclusion to his work, where he comes to the conclusion that “The only thing that matters is the theater, and not necessarily anything else.” It's a sad conclusion that is obviously rooted in the past trauma (by the films own admittance) of his abusive relationship with his Lutheran pastor father that stands as the odd one out in a body of work so rich and spiritual. Fanny and Alexander is undeniably well made and epic, but not necessarily optimal in its messaging.

Ultimately, the cinema of Ingmar Bergman is a catalog that serves to challenge us in about every way art can challenge an individual, and be beneficial. Bergman, as an absolute master of his craft, gave us a massive list of masterpieces to explore ourselves with and further our spiritual development. He challenged the way the world saw cinema, and was willing to explore places that no one else would dare to go near, making us all the better by doing so. His intense focus on the human spirit and psyche certainly has inspired many to follow in his footsteps and deepen their relationships with God and others. With this being said, we enthusiastically introduce to you 5 must see films from his catalog, although the list could very easily be much longer.