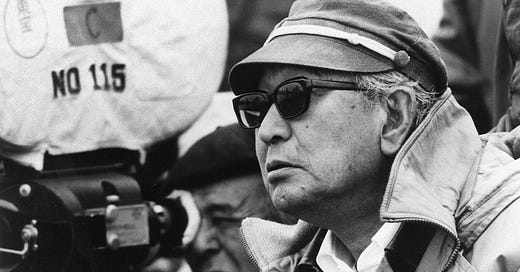

Introducing '100 More Movies' Series #2: The Films of Akira Kurosawa

Exploring the works of the Japanese master of cinema

Following our series on John Ford, we are now excited to announce our next filmmaker deep dive for the list, exploring the films of legendary Japanese director Akira Kurosawa.

There are few (if any) filmmakers that can compete with the artistic brilliance of Akira Kurosawa. The very name is one that is justly etched into the minds of movie fans from around the world, and if there were a Mount Rushmore for auteurs, Kurosawa would easily make it on. There is perhaps no other filmmaker who had the longevity, consistency and quality that Akira had over the course of 7 decades and more than 30 films. Kurosawa’s filmography offers film fans, and especially Catholics, a deeper look into the art form and ourselves, with a wide range of stories and settings to help.

Akira Kurosawa lived through a tumultuous time in history. Similar to Servant of God Takashi Nagai, he was born in the first decade of 20th century Japan, and had to endure the trials and tribulations of the Second World War. While Akira had a late start in film due to the war and other external factors, he nevertheless began to make a name for himself within Japan in the late stages of WWII and in the immediate aftermath. Early on in Kurosawa’s career, he began working with the actors who would be synonymous with his work and legends of cinema. Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura started very early on in Drunken Angel and Stray Dogs, whose plot seems like something out of a Dovstoyevsky novel.

Soon after, he would go on to make his breakthrough film that would catapult him onto the world stage, and shake film so much it is the reason the Academy Awards now have a Best Foreign Language Film award: Rashomon. Based on the Japanese short story In the Bamboo Grove, it is the origin of the term “Rashomon effect”, where multiple individuals will tell different versions of the same event and cannot seem to agree on what occurred. Rashomon established to the world that Kurosawa had more to say not only to make a buck at the box office, but to say something about humanity.

Rashomon also began what is perhaps the greatest and most prolific run any filmmaker ever has and ever will have. Over the course of the 15 year span from 1950 to 1965, Kurosawa made 13 films, averaging a movie every 14 months. The films in this stretch of time would define cinema as a whole, and leave profound impacts on audiences around the world. My personal favorite of the era changes, but Ikiru continues to pull for my favorite, demonstrating Kurosawa’s passion and belief in the goodness that can lie within the human spirit, and the beauty that a quiet, selfless act can have on others.

After Rashomon was his adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot. This would also establish his affinity for Western media. Kurosawa was obsessed with Western media and culture. It shaped his storytelling, his thoughts and beliefs, his world view. His love of Russian literature (also shared by his dear friend Andrei Tarkovsky) and his love of Shakespeare had unmistakable effects on his art, with the latter being adapted thrice by him. Kurosawa noted in his autobiography the profound impact the films of John Ford had on him and his desire to try to match him. The Ford Westerns shaped Kurosawa to help give birth to Japan’s own version of the western: the Samurai film.

Feudal Japan became Kurosawa’s preferred canvas. Seven of his films from the 1950-1965 era were samurai films, and among the best ever made. Films like Seven Samurai and Yojimbo changed film forever. Akira took things to a whole new level of artistic vision within this subgenre, and unintentionally set the standard for action films moving forward. His samurai films went on to reinspire the Western genre, science fiction (his excellent adventure film The Hidden Fortress being the primary inspiration for Star Wars), and the action genre overall with their pacing, heart, and depth. While many aspire to reach Kurosawa’s level of prowess, none have matched it.

Also within this “High Kurosawa era” of 1950 to 1965 lay 2 excellent retellings of Shakespeare plays, with Throne of Blood retelling Macbeth and The Bad Sleep Well retelling Hamlet. Both are excellent examples of recontextualized Shakespeare within different settings done properly, and are rightfully considered some of the best adaptations of Shakespeare’s timeless stories.

Every film in this High Kurosawa Era has great artistic value, and I would be remiss if I finally did not mention one of the crown jewels of the era; High and Low. High and Low delves into a moral and existential thriller about a rich oligarch whose servant’s child is mistakenly kidnapped when his child was the intended target. Just as all films prior, Kurosawa does not shy away from asking the audience difficult questions, but using ugly situations to bring out the best in people, and tells it will be brilliant craftsmanship.

After the High era, Kurosawa suffered a series of setbacks. He struggled to find financial backing for projects, and his struggle with depression began to worsen. In 1971, he attempted his own life, but survived the ordeal thankfully. This Late Kurosawa era was when Kurosawa drifted more towards gloom rather than optimism, and struggled with existential dread. His films are desperately searching for answers and undeniably have pessimism throughout, but in all of it there is still hope to some extent. Late Kurosawa is also defined by perhaps the best use of color photography ever made. Up until this point, all of his films were remarkably shot in black and white, but with his Late era, it feels somehow even more glorious than Technicolor. His films in this era were also primarily funded by George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, who wished to return their affection for inspiring them. Late Kurosawa era is equal parts haunting, tragic, and beautiful. Kagemusha, Dersu Uzala (the most optimistic of the bunch and recognized by the Vatican), Ran, and Dreams are all essential viewing experiences.

In particular, I want to discuss Ran. While it is not on the list, it is one of the most quintessential pieces of cinema ever made. Being an adaptation of King Lear while borrowing a few elements from Macbeth, it is perhaps his most tragic, beautiful,and haunting film ever made. With every frame being painted by hand by Kurosawa before shooting, it is a visual marvel to be witnessed, and in my opinion the greatest Shakespeare film adaptation. It feels desolate, epic, and intimate without preaching. It is Kurosawa, having lived his life and witnessed a century of horror, trying to make sense of it all. In his final film Dreams, he was thankfully able to find some consolation, and underscores the value that spirituality and belief can give to life, as well as the creation of art, which is reminiscent of his dear friend Tarkovsky’s sentiment, who had passed away recently. Kurosawa would pass away in 1998 of natural causes, leaving behind an illustrious body of work that will be forever revered.

So after all this, it is apparent as to why as a film lover one should watch his films, by why Catholics? Kurosawa, while agnostic himself, believed in people and goodness. His films frequently discuss or hint at the existence of the spiritual world. Kurosawa was obviously familiar and well versed with his own culture, but managed to tell universal stories within the context of what was familiar to him. His incredible control of movement, the camera, and his ability to pick and adapt stories of meaning has allowed movie goers across generations to empathize with his art. The art of Akira Kurosawa is not a nonreligious person mocking those who believe, but rather a deeply spiritual person desperately searching for answers. We as Catholics are able to fill in these gaps and can take comfort in our Lord, but we can learn so much from Kurosawa’s stories just as we can from say ancient myths or Aesop’s fables. All of his films hold a deep belief in the human spirit and just understands people and storytelling. With all of his stories he allows us to laugh, cry, think, cheer and anticipate every scene, offering a holistic and true cinematic experience.

There is no such thing as a bad Kurosawa film. His name is a mark of quality and excellence. As we go through in further detail some of his key films, I highly implore you to go even further, and that anything with his name attached is made to impress. There is something to be enjoyed, marveled, and learned in his seven-decade, 30+ year film career for all the faithful and film lovers, and I cannot wait for you to start the journey with him.

Great and inspiring essay here! I actually recommend Ran to a friend yesterday and have been meaning to get back into him. The pacing and use of natural elements in his films (earth, wind, fire, water) give them such an enduring texture that holds up well decades later.

Ran, like its source, is beautifully and subversively Catholic... An absolute masterpiece... He set it in the Sakoku period (after Japan rejected the Faith) for obvious reasons... Don't believe my theory? Just rewatch the final scene. Buddha falls helplessly away. Zoom out and framing the desolation is two felled crosses. It's in our faces... Kurosawa was infamously coy about his beliefs. I don't think it's too far fetched to suppose he could have been less-than-agnostic in his later years.