For all of Wes Anderson’s artificial gimmicks he has become famously (or infamously) known for, his true interest as a filmmaker has always been with the emotionally icy characters that populate his colorful dollhouse world-building. With his early films (The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, The Darjeeling Limited) Wes focused on the artifice of filmmaking, but also the artifice of relationships where characters rarely revealed their hearts. His characters were charming, quirky, sometimes infuriating with their refusal to communicate their emotions, but who found comfort in the rare moments of connection with each other.

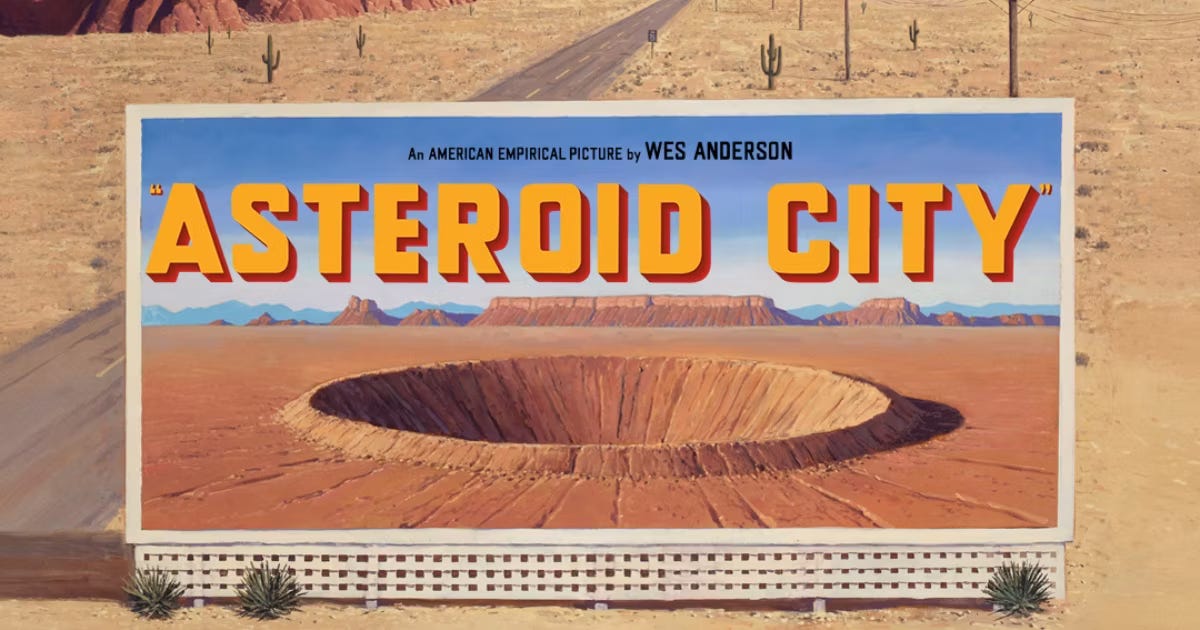

As the years went by, Wes became more interested in the state of the world and, for better or worse, his movies became bigger in scope, more meticulous in design, but sometimes less focused on character. So I’m happy to report that his latest creation Asteroid City, while still full of Anderson’s obsessive flourishes and a bigger-than-usual ensemble, returns the focus to character drama, and for the most part, it works.

To explain how the film operates is a headache, but necessary. The film is presented as a black-and-white television show about a playwright (Edward Norton) and the creation of his newest work, Asteroid City. The tv program is a documentary of sorts, charting the casting and performing of the play. The actors who are playing the parts soon become the real characters they’re playing, and eventually, the film becomes a real-life colorized recreation of the play being performed on the tv show. If it sounds confusing, it is. But bear with me.

The action of the play-within-the-tv-show takes place in the 1950’s in the titular town, home to a massive crater and an annual science convention. Among the families to attend the convention are war photographer Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman) and his son Woodrow (Jake Ryan), and famous actress Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson) and her daughter. While other families attend and create a complex diorama of unique characters, Anderson gives audiences the privilege of having two leads, Augie and Midge, to focus on this time.

Augie lost his wife three weeks prior, but has only just now decided to tell his children. He carries the ashes of his deceased wife in a Tupperware container, unsure what to do with her. Having lost faith in God, Augie is emotionally, spiritually aimless, a trait he soon passes on to his son Woodrow.

Midge has been in a series of unsuccessful relationships, and has other children elsewhere but rarely sees them. She spends her time practicing for plays of a tragic nature, but never displays any real emotion about her pain (a common Wes trope). It’s as if Wes heard the voices of his critics mocking his characters’ emotionally flat way of speaking, because he positions Midge and Augie’s conversations in the most visually symbolic way possible. They spend most of the film communicating from separate houses, looking at each other from their respective windows. She practices her plays and he prints his photos, both using art to express the unexpressed. Why do his characters never speak about their pain directly? Wes has Midge answer the critics: “we’re two catastrophically wounded people who don’t express the depths of their pain because we don’t want to.”

With icy precision, Midge puts into words the emotional and spiritual desolation of these characters, and of Wes Anderson’s latest film in general. This desolation is captured visually in the desert landscape and the enormous crater. Bombs occasionally go off in the distance, one in particular just before Augie tells his kids their mom is dead. His visual language has never been more precise, and he uses his colorful toolbox to heighten the emptiness (and sometimes hilarity) of a world that has lost sight of its purpose. Even though everyone is gathering for a convention with goals of fame and success, no one is happy, because no one is connected. Emptiness pervades. St. Ignatius describes spiritual desolation as a movement away from God, characterized by a lack of hope, a lack of confidence, and a lack of peace. This is true of almost every character in the film, but unlike St. Ignatius, none of these sad souls find an opposite consolation in God, continuing only a downward spiral.

When the alien finally lands (yes, we get a very funny alien encounter), the town is thrown into quarantine while the government frantically tries to understand the encounter.

Within the isolation of the desert emerges a desire for understanding, something no one is equipped to give. Some of the most charming sequences involve a schoolteacher and her pupils who come to the town for a field trip. The teacher tries to follow the lesson plan but the kids only want to know about the alien. The public educator is not prepared to answer these questions about the universe, and must rely on the wisdom of a local cowboy to give the kids reassurance. He gives them simple wisdom about accepting the unknown, inspiring one student to write a song about it that sings, “oh alien, who art in heaven...”

The simple desire for understanding is present everywhere, and even a desire for faith creeps into the film, but all the expressions of belief in the movie, whether Christian or atheist, feel incomplete, just like the town.

This lack of understanding eventually drives the residents crazy, not to mention being under lockdown (this is definitely Wes Anderson’s post-covid movie). By the time the government issues a second quarantine, the people still don’t know anything and fight back in a hysterically chaotic brawl. This revolt against the incompetent government is one of the most cathartic movie moments in recent memory.

Yet even after the revolt, there is still a general disillusionment, perhaps more so, since no one in charge provides guidance. Parents have emotionally abandoned children, the government is ineffective, and the teachers aren’t helpful. Even the tv show about the play reveals that the writer himself wasn’t entirely sure what the play meant, and that the creation of the Asteroid City came about through questionable means, including an actor buying a lead part through sodomy with the writer, a director only being available because his wife divorced him, and the main child actor being chosen due to random favoritism. By the time the conclusion is reached, the lead actor still does not understand his part, and consults the director. He tells him, “I still don’t know what the play is about.” The response the director gives him is perhaps illuminating; “it doesn’t matter,” he says, “just keep telling the story.”

Despite Wes viewing the current state of the world as spiritually desolate (and he’s right to a degree), he sees the importance of continuing to tell the story, in continuing to live. As characters hop in their cars and leave Asteroid City, their destinations are unknown, but a newfound purpose has arrived. The importance of telling the story is even reflected in Wes’ meta-narrative. The story of the play itself is told, but so is the behind-the-scenes drama, and all of this is broadcast on tv to share with the world. Through each layer, Wes reveals the way storytelling continues and changes throughout time, and in an ideal world, can bring people closer, just as Augie and Midge sharing stories through their window screens brings them closer together by the end. We may have reached a day where society has blown up with only an empty crater left in its place, but as long as people remain to tell stories to each other, we can still attempt to understand the unknown.

Content Advisory: a brief homosexual kiss between two minor characters, a brief moment of discreet nudity, some course language and comic violence. A callous view towards God and religion from some characters.