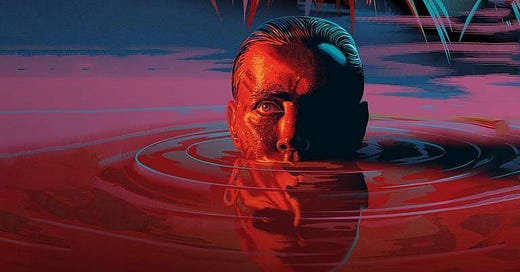

100 Movies Every Catholic Should See #51: Apocalypse Now (1979)

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Starring Martin Sheen and Marlon Brando.

This is the end

Beautiful friend

This is the end

My only friend, the end

A napalm-fueled firestorm envelopes the frame. As smoke billows around us, the strains of The Door’s psychedelic rock hit “The End” become audible, evoking the song of the muse at the beginning of epics far across history. This will be no ordinary film. We have been warned. A viewing of Apocalypse Now invites audiences on a dark and harrowing journey across thousands of miles of untamed wilderness to the deepest recesses of the human psyche, an experience that has oft been compared with Dante’s Inferno. A brilliant fusion of vibrant cinematography, meticulous direction, and iconic performances has created one of the defining events of cinema, an archetypical evocation of man teetering on the abyss.

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself in a dark wilderness,

for I had wandered from the straight and true.

Apocalypse Now draws its origins from Joseph Conrad’s controversial 1899 novella, Heart of Darkness, a vast and chilling tale that filmmakers had struggled for decades to bring to the big screen. The first to try was Orson Wells, young and ambitious and coming off a successful series of radio programs. Even with all his energy behind the project, studios balked at the massive price tag and rigorous demands of shooting in far flung locations. The project was deemed unfilmable. In a fortuitous twist of cinematic fate, Orson Wells turned to his next project, a little film called Citizen Kane which you may have heard of.

The idea of a Heart of Darkness never died out completely, it percolated, waiting for the opportune moment and a new director, willing to take upon himself the challenge of bringing this dark and demanding saga to life. The fresh winds of change came in the early 1970s when the old studio system gave way to America’s “New Hollywood” movement. With it, a fresh generation of young, maverick directors were emboldened to embrace new challenges and push the envelope further than ever before. Enticed by what had been deemed impossible, one such member, Francis Ford Coppola, decided to attempt the adaptation. It was, as one former professor of his described, "waving a red flag" in front of the proverbial bull.

A film of such unique and unparalleled aesthetic character would not have been possible without Coppola’s total artistic control over the entire production. Two lucrative Godfather films gave him the means. Such creative autonomy had the ability to yield wild and wholly unique results, often through harrowing, risk-laden production experiences. The story of the making of Apocalypse Now rivals the subject matter itself in its almost mythic notoriety. Battling typhoons, a local civil war, strife within the crew and a near fatal heart attack of lead actor Martin Sheen, the film’s production struggled forward, deep within the jungles of the Philippines. The ordeal is masterfully chronicled in Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse, an enlightening documentary which I wholeheartedly recommend as supplemental material to the film. It is through these real life horrors that such a gritty and visceral exhibition was able to be put on screen.

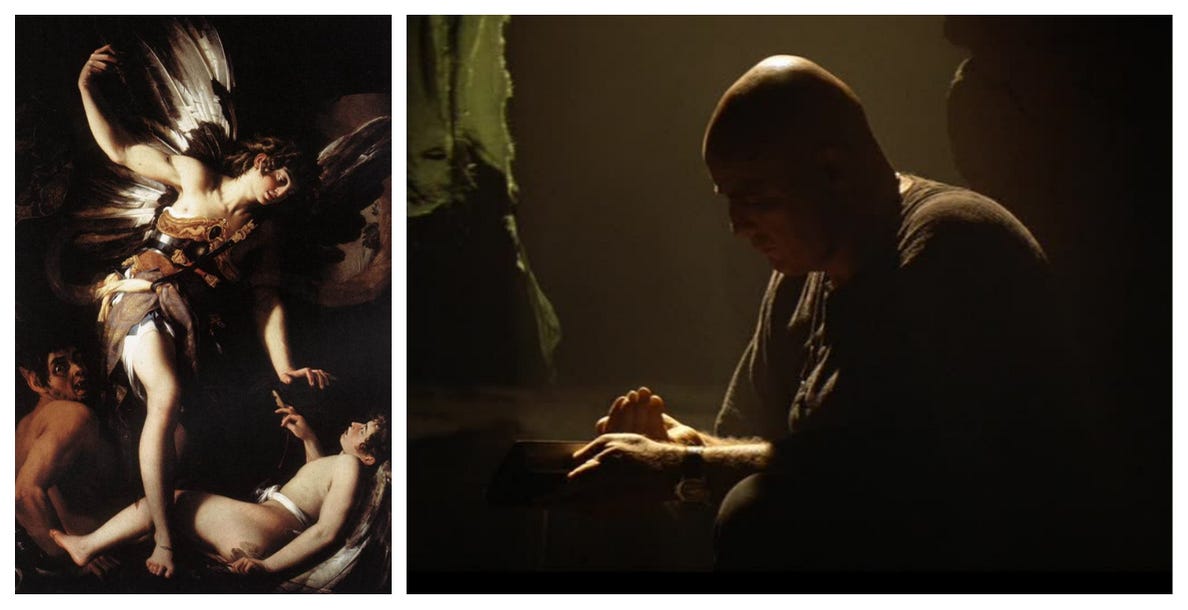

Equally potent in building the film’s profound dramatic qualities is cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s evocation of classical art, particularly in the imitation of Tenebrism and Chiaroscuro, Baroque techniques used to accentuate extreme contrasts between light and dark. These effects evoke a strong emotional response, giving the sense that one is in an almost mythic and archetypal realm. In the final act of the film, Storaro shoots exclusively in this style, signaling that the protagonist has reached the conclusion of his journey and must contend with the dark realities that have awaited him his entire journey.

What lends profound impact and universality to the film lies in the evocation of the hero’s journey, a trek across vast distances physically and a foray into the innermost depths of the human psyche. The narrative follows Captain Benjamin Willard, a soldier languishing between action in the Vietnam war, who is assigned a secret mission to find and terminate a former colonel, who has gone rogue deep within the jungles of Vietnam. “Your mission is to proceed up the Nung River in a Navy patrol boat. Pick up Colonel Kurtz's path at Nu Mung Ba, follow it and learn what you can along the way. When you find the Colonel, infiltrate his team by whatever means available and terminate the Colonel's command.” But really, the mission becomes Willard’s journey inward to contend with his own “Heart of Darkness”.

Willard’s voyage into the deep jungles mirrors Dante’s descent into the inferno in the first part of the Divine Comedy. Mankind teeters on the brink of chaos. War has enveloped and shaken Willard’s world. The order of the world has been stripped away and each man has been forced to contend with the chaos in his own way. Applying a Catholic lens, I would argue that this chaos could also be seen as a certain Godlessness, inherent in the age. It's something T.S. Elliot’s “Hollow Man” embodies, a connection Colonel Kurtz makes at the end of the film. As Willard journeys deeper upriver, he comes across a variety of characters, each who have chosen to react in a unique manner to the horrors of the war and by extension, the embrace of their own hearts of darkness brought about the collapse of humanity’s moral compass. In the Inferno, Dante must encounter an assortment of sinners, each who have chosen a particular aspect of their own inner darkness in turning away from God’s order.

The term "Apocalypse" finds its roots in the Greek word 'apokalupsis,' meaning an "unveiling" or "revelation." Dante is pulled away from his path deviancy to confront the entirety of sin revealed in the Inferno. Forced out of his own dissipation, Willard’s journey ultimately becomes a revelation of the darker aspects of human nature. The “Apocalypse” in Apocalypse Now thus becomes a confrontation with the breakdown of human sanity, a moral Armageddon.

Reading Apocalypse Now in the light of Dante’s Inferno can help elucidate a deeper moral understanding of the film. The purpose of the Inferno was never to revel in sin, but rather help one to recognize and ultimately dissociate from their sinful nature. Willard, in turn, is forced to come face-to-face with the darkness present within himself. Whether he chooses to embrace it or reject it remains unclear. But Coppola cannot entirely escape from the faith in which he was raised. As is often the case with directors coming from a Catholic upbringing, palpable echoes of that worldview remain, making for an enriching and informative experience as Catholic filmgoers.

Apocalypse Now represents a singular and unparalleled entry into cinema’s canon of great films. Epic in scope, the film covers great distances both in physicality and in psychological introspection. Upon closer investigation, a fascinating moral element emerges, providing ample material for thoughtful Catholic viewers For those bold enough to take the challenge, it is an unforgettable cinematic experience.