100 Movies Every Catholic Should See #19: Gravity (2013)

Directed by Alfonso Cuarón. Written by Alfonso and Jonás Cuarón. Starring Sandra Bullock, George Clooney.

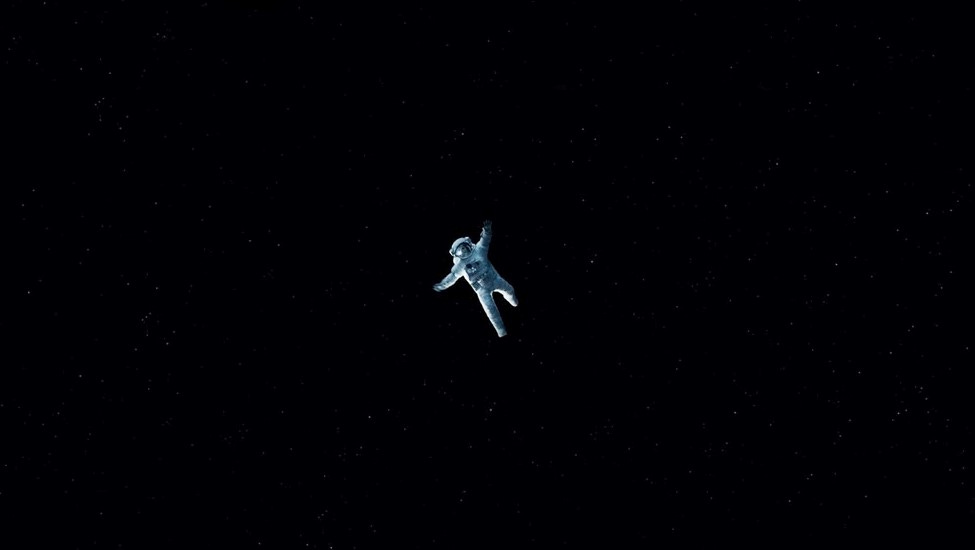

The story of a soul adrift.

*spoilers ahead*

Gravity begins with an impressive thirteen-minute long tracking shot that gives viewers a glimpse of their home planet from a distant vantage point. Immediately, audiences are immersed into outer space and feel everything from the perspective of the astronaut protagonist Dr. Stone (a gripping portrayal from Sandra Bullock). With the opening camera shot never breaking, but only drifting slightly, the sensation of weightlessness becomes real. While the feeling of floating in space can sound liberating, the truth is that an astronaut is severely limited in space travel. Not liberated at all, they are fully dependent on technology for survival. Space is vast, endless, but ironically limited for what a person can do or achieve because of human limitations. People can stare in wonder and awe at space travel and what humankind has been able to accomplish with man-made technology, but the further people drift from their earthly home, the less capable they are of surviving. The ambitious man seeks to conquer the stars, but more often than not, the stars conquer him. In the case of Gravity, the realization soon sets in that space will never be a place man can truly find peace.

Director Alfonso Cuaron (Children of Men) began an unofficial trend in 2013 that some circles have jokingly labeled “the sadstronaut” trend, describing films that center on an emotionally wounded astronaut navigating the perils of space - and the hardships of life. Gravity had the benefit of starting the trend that was shortly followed with Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Ridley Scott’s The Martian, James Gray’s Ad Astra, and so forth. While these later films can be praised for their complexity and technical achievements, it’s worth recognizing the leanness of Cuaron’s vision, where he not only creates the most immersive cinematic outer space experience since Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but, in a brisk ninety-one minutes and with only two actors, takes viewers on an emotional roller-coaster into the mind and soul of a woman spiritually adrift, struggling to find faith again in the wake of a tragedy.

Sandra Bullock’s Dr. Stone, a new astronaut on her first space mission, is accompanying veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), to make hardware repairs on the Hubble Space Telescope. The opening scene establishes her ingenuity and skill at her job, but also her novice status and her reliance on Kowalski for guidance. They banter about work while drifting through space, and while all seems peaceful, there is a general feeling of unease, knowing the peril and complexity of mechanical repairs while wearing a spacesuit (the image of a screw floating away offers simple foreshadowing). Within the first ten minutes, the film goes from serene beauty to heart-stopping tension when the astronauts are hit with space debris caused by the Russians shooting down a defunct spy satellite. The cascading impact of the debris causes Dr. Stone to be torn from their shuttle, leaving her helplessly floating in space. Cuaron orchestrates the chaotic debris with a master’s hands, filling the screen with the spacecraft’s destruction but never losing sight of the protagonist, even seamlessly moving the shot inside her helmet to create a first-person view of the character tumbling through space with no support. It’s a bold, frightening sequence that immediately sets the stakes high and rarely lets up on the tension.

Immediately after Stone is rescued by Kowalski (a sort of guardian angel figure), they begin their slow journey drifting towards the International Space Station, where they will plan their eventual return to earth. It’s a moment of calm after the chaos, but the stakes have been elevated and Stone is running out of oxygen. Trying to keep her calm and focused on her mission to get to the space station, Kowalski begins to question Stone on the reasons why she decided to leave earth for space. It is here Stone reveals her past, and that her daughter died in an accident when she was only four. Heartbroken and confused that something so tragic could happen with seeming randomness, she turned inward and retreated from the world. She now prefers the quiet of space away from the memory of her terrible loss. With Kowalski guiding her towards safety, and the revelation of Stone’s traumatic history, the spiritual dimension of the film starts to reveal itself. Stone is not just on a journey back to earth and safety, but is on a journey to heal her soul and discover a second chance at life, and acknowledging her loss was only her first step.

Cuaron uses stunning visual language as metaphor for Stone’s journey back to faith, and cleverly illustrates many ironies of faith as well. The measurable, scientific world is where Dr. Stone has immersed herself because it is a tangible reality, but by placing the setting in space, the measurable proves to not always be reliable, and as it turns out, the physical can be deeply destructive. Each attack of debris becomes a symbol of Dr. Stone frantically trying to navigate the sorrow and dangers of life while looking for something, anything, to hold onto. She is surrounded by the man-made scientific world, but constantly adrift, unable to anchor herself on science alone. In a dramatic moment, when debris strikes again near the ISS, Kowalski asks Stone to take a leap of faith by letting go of the cord holding them together. She refuses, but Kowalski pushes her to do it, knowing she needs this moment of faith to reach safety. It is a true irony of the Christian faith that in order to find peace of heart we must first let go of what we cling to. To find ourselves, we must lose ourselves. Cuaron places Stone in this moment of danger, letting her drift alone, in order for her to enter the ISS craft and find stability again. This leap of faith allows Stone to begin her “rebirth” and in one of the film’s most memorable images (courtesy of master cinematographer Emmanuel Lubeski), Stone floats in the ISS craft in fetal position with a cord dangling behind her, creating the image of a child in the womb. She is still not ready to begin life anew again, but she has made the leap, and begun the process of spiritual rebirth.

Catholics will point out that later during Stone’s journey, when she enters the Russian craft, there brief glimpse of a Saint Christopher icon, carrying the Christ child over the waters. While the theme of spiritual renewal is universal and not limited to Catholicism (the Chinese craft contains a small statue of Buddha), the inclusion of Saint Christopher is not insignificant. Saint Christopher is the patron Saint of travelers, and while his sainthood is more of a legend and not officially included in the Church’s universal calendar anymore, he is still a commonly invoked saint, and his brief inclusion in Gravity comes at a pivotal point in her spiritual journey. Stone finds herself in a moment of desperation and, breaking down in tears, realizes that no one ever taught her how to pray. Despite this, her cries are the prayers of a woman no longer clinging to the man-made, but reaching for something transcendent, even though she does not fully understand it yet. This scene can be read as a symbolic invocation to the patron saint of travelers, begging him to help her cross the remainder of space and return home. As she tearfully drifts off to sleep, she is visited by Kowalski in a dream, further suggesting his character as a spiritual mediator, giving her a moment of divine intervention. His presence gives her strength and wisdom to awake and continue the journey, her prayers answered.

In her final descent towards earth, there is uncertainty about survival, and Stone realizes these may be her final moments of life. But as she descends, she remembers her daughter and presses on. The pain of loss originally led Stone to retreat into herself, but in the memory of her daughter, she finds strength instead of weakness, courage instead of fear. Running from the memory caused Stone to drift, but now facing the memory, she at last is ready to re-enter earth’s atmosphere. The final visual metaphor Cuaron presents is enough to bring tears to the eyes. As the craft hits the water, Stone is submerged, going from the vastness of space to the vastness of the deep. Removing her suit, she is freed from the waters (a symbol of birth) and floats to the shore, touching the ground for the first time in the film, finally experiencing the earth’s gravitational pull. After the chaos and constant peril of space, there is a stillness at last, and she is able to rest. As she holds the ground close to her body, she utters a quiet “thank you.” This thank you feels in answer to the divine intervention that occurred throughout her journey, and an acknowledgment of the spiritual dimension she once sought to avoid. Taking her first shaky step on earth, she is unsteady like an infant, but gains balance and stands triumphantly, completing her journey. In the final irony of faith, letting go of the pain of earth allowed her to embrace life on earth once more, and despite the spiritual not being a tangible reality, embracing the spiritual gave her an anchor, gave her gravity.

Cuaron’s triumphant story of the human spirit was praised for its technical achievements and award-winning central performance, and the film is memorable today for its jaw-dropping outer space sequences, but these final moments on earth reveal the subtext of the entire film, and seal it as one of the most moving pieces of twenty-first century popular art. The soul is lost without God, drifting aimlessly in the darkness, and only with the power of faith can the soul find its way home again.

“You have made us for Yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in You.” - St. Augustine.